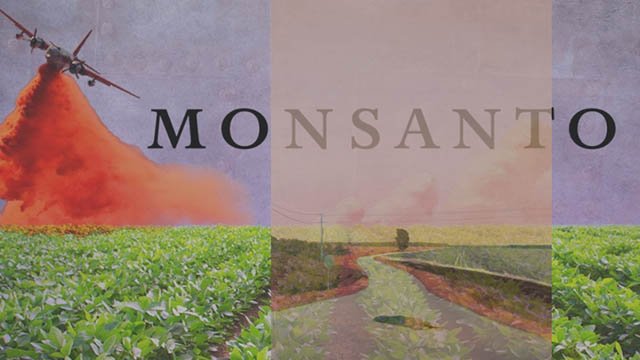

Monsanto’s new herbicide was supposed to save U.S. farmers from financial ruin. Instead, it upended the agriculture industry, pitting neighbor against neighbor in a struggle for survival.

Originally published in The New Republic by BOYCE UPHOLT

Mike Wallace sat in his pickup truck on a dusty back road near his farm outside Leachville, Arkansas, typing impatiently into his cell phone. “I’m waiting on you,” he wrote. “You coming?” It was hot for late October. The rows of soybeans, cotton, and corn, which just days ago had spread across much of the region, were largely gone, replaced by dry, flat dirt. The 2016 harvesting season was nearly over. A minute passed, and Wallace typed another message, sounding slightly triumphant. “Looks like you don’t have much to say now.

Wallace, 55, was a prominent figure in the Arkansas Delta farming community. His 5,000-acre farm was large, although the yield on that year’s soybean crop hadn’t been as successful as he had expected. Wallace believed he knew why his crops had failed, and it had nothing to do with the sun or the rain or the decisions he had made about when to put his seeds in the ground. Instead, he blamed a 26-year-old farmhand named Curtis Jones for illegally spraying dicamba, a controversial weed killer, on a neighboring farm. Wallace believed the dicamba had drifted onto his fields and damaged almost half of his soybean crop, costing him hundreds of thousands of dollars.

It wasn’t the first time this had occurred. The previous year, dicamba from another farm had also drifted onto Wallace’s fields, causing the leaves of his soybeans to pucker into ugly cups fringed with white fuzz. He complained to the Arkansas State Plant Board, which oversees such disputes. The agency fined Wallace’s neighbor, but Wallace was never compensated for the lost revenue. So when Wallace was hit again the next season, he decided he’d had enough. He called Jones and proposed that they meet to settle things in person. Wallace threatened to “whip [my] ass,” Jones later said.

Moments after Wallace sent his last text message, Jones arrived in his own pickup. As soon as he stepped out of the truck, Jones later told police, Wallace charged at him, arms flailing. He was on Jones within seconds, pinning him against the rear driver’s side door. As they scuffled, Jones pulled a .32 caliber semiautomatic pistol from his back pocket and began to fire. The bullets hit Wallace in his right shoulder and arm, his chest, and abdomen. Jones continued firing until the clip was empty—seven shots in all. One bullet entered Wallace’s back, above his left buttocks. Just 91 seconds after Wallace’s last text message, Jones was on the phone with police to report that he’d shot a man. Wallace lay in the dirt, bleeding to death.